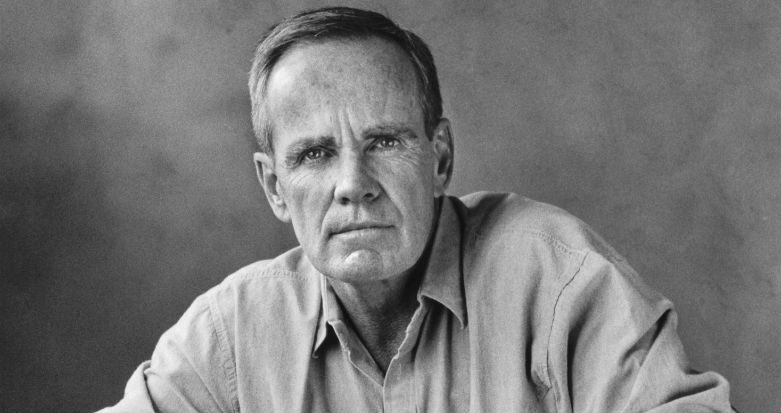

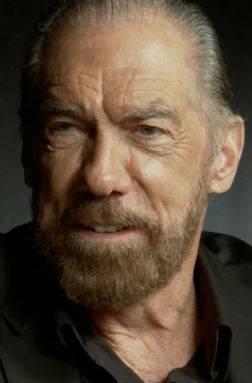

El Paso, West Texas, where the Rio Grande runs the border between the United States and Mexico. In Luby’s Cafeteria alone at a window table sits Cormac McCarthy. Soup, coffee. Straight-backed in his tweed jacket. Wearing his spectacles to read his newspaper.

McCarthy had a few favourite haunts around town: the Village Inn for breakfast, late lunch or dinner at Luby’s, shooting pool and eating Mexican food in the old quarter. He liked a bookstore 40 miles away in Mesilla, where he bought non-fiction on frontier history. He lived in the suburbs by a shopping mall – a single-story, pueblo-style building.

Related:

The cult of Pablo Escobar: EDGAR profiles the ruthless Mexican drug lord

The sad demise of Ernest Hemingway

“Surviving the Titanic ruined my life” - the incredible story of J. Bruce Ismay

Had McCarthy spoken with the staff at any of these places, he would have heard there was a guy from out of town asking questions about him. Had McCarthy been in touch with his lawyer, his friends, his ex-girlfriend, his ex-wife, he would’ve found out about the young journalist from London who’d flown 5,000 miles to find him. Had McCarthy been home when this journalist was knocking on his door, waiting outside his house, making notes on the pickup trucks he drove, he would’ve known how serious Mick Brown was about meeting him.

The Luby’s restaurant in El Paso where Brown met McCarthy.

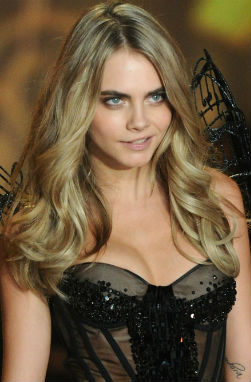

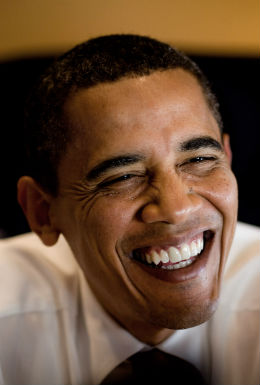

If McCarthy did know, he didn’t show it when Brown walked into Luby’s and up to his table. This was 1994. The American writer had lived in El Paso for 15 years. McCarthy, at that time, had written seven books in a three-decade career that was only just beginning to bring him commercial success to match his critical acclaim. In his whole career he’d given just one interview. His conversation with Brown – published in UK broadsheet the Sunday Telegraph – would for many years count as the most he was willing to interact with the press.

McCarthy listened as Brown explained who he was and how he’d very much like to talk with him. McCarthy eyed his cup. Maybe, like one of his characters, he sat stirring the coffee with his spoon – though there was nothing to stir since he drank it black.

“I’m sorry, son,” McCarthy said. “But you’re asking me to do something I just can’t do. I’m just not in the writing business, you know? If I’d known all this was going to happen, I’m not sure I’d have even started. I appreciate you’ve come a long way… But I just can’t do this thing.”

Brown recalls McCarthy making it sound like the decision was out of his hands. “I remember wondering if I should even approach him at all,” the journalist says. “It seemed like a violation of his privacy. But I’d come too far not to talk to him. I didn’t for one moment expect him to agree to talk to me. I was astonished to find him in the first place. He couldn’t have been more gracious – nor more adamant that he wouldn’t grant me an interview. Part of me was disappointed, of course. But on the other hand it seemed curiously appropriate. His mystique was preserved.”

And what mystique. McCarthy – the world’s greatest living writer – rejects in every way the literary world which holds him so dear. You can count on one hand his public appearances. He doesn’t give talks, attend signings, write journalism. He has never talked about his writing in any detail.

Yet he is one of the most talked-about, most decorated, most academically analysed literary figures working today. His most recent novel, The Road, earned him the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. The Orchard Keeper won the 1966 William Faulkner Foundation Award for a first novel. He hasn’t written a bad book between them.

His words cut like a knife to our baser instincts, to the most brutal, primitive parts of the human condition. His sentences spill blood – averaging a murder every five pages at their bloodiest – and his stories stay with us long after we leave them: haunting us with the combined force of all the spectres of all the souls slain across his pages. McCarthy simply wipes clean the knife as he steps away from the typewriter. It’s our job to make sense of the bloodshed.

The film adaptation of The Road.

The Wingshot

“Years ago,” John Sepich says, “probably our first conversation, I said he must go into a heightened state to be able to write the way he does. And McCarthy told me a story of a wingshot, a dove hunter, who could hit any bird that flew, and that a farmer, on whose land he was hunting, stopped him and asked did he keep his left eye open when he shot, or did he hold it closed? And that the man said he didn’t know, but he’d think about it. And McCarthy said the man never hit another dove again. So I thought about that and said into the phone, ‘God, now I’ve done it. Talking to the best writer I’ve ever met – now with my question he’ll never write again.’ And he sort of chuckled.”

Sepich’s Notes on Blood Meridian was one of the first books of criticism ever written on McCarthy. He finds most fascinating how McCarthy’s characters never reveal their motives: “McCarthy has said he writes of people and events he’s ‘seen and heard tell of’. You don’t hear the interior monologues of people you see on the street. McCarthy doesn’t make up motivations for the people he’s ‘heard tell of’. His stories are of what people do, what they say, and what happens to them afterward.”

The author is the father of the character. And McCarthy himself is as unforthcoming as his players. Some say Cormac is a family nickname – one shared by Charles McCarthy senior and junior. Others that the younger Charles renamed himself Cormac after an Irish king. We do know his father was a lawyer who took a job with the Tennessee Valley Authority when he was four.

Javier Bardem in No Country For Old Men.

He grew up in Knoxville, the third of six children. His family was well-off. He twice attended the University of Tennessee and left both times without completing his studies. Disputed also is whether or not he left of his own volition. In between stints at university he spent four years in the US Air Force – two in Alaska. It was here, largely to kill time, he began to read with voracity.

His second spell at the University of Tennessee yielded his first fiction: two short stories. He was twice awarded the Ingram-Merrill Award for creative writing. For the next quarter century – funded mostly by money from prizes, grants, fellowships – he lived a peripatetic life.

McCarthy’s characters are wanderers or outcasts. They often belong to another time. In All the Pretty Horses, John Grady Cole feels most at home in the saddle, on the plains. The 16-year-old leaves home on horseback with a friend. They ride from Texas into Mexico to live as cowboys. The Crossing’s Billy Parham catches and attempts to release back into the wild a she-wolf that’s been attacking local cattle. Lester Ballard – Child of God – lives feral in a cave. As he becomes more isolated from society he commits increasingly depraved crimes.

“I was not what they had in mind,” McCarthy said about his childhood relationship with his parents. “I felt early on I wasn’t going to be a respectable citizen.”

McCarthy moved around the US throughout the early ’60s. He married, had a son, divorced. He finished first novel The Orchard Keeper and sent the manuscript to Random House: “It was,” he would later say, “the only publisher I had heard of.” It found the desk of Albert Erskine, William Faulkner’s old editor. Under Erskine’s editorship, McCarthy earned a travelling fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and left for Ireland.

On the boat over he met Anne DeLisle. They married in England in 1966 and travelled Europe on his Rockefeller Foundation grant, briefly settling in an artists’ commune on Balearic island Ibiza. Here McCarthy worked on second novel Outer Dark. They returned to Tennessee and settled in Rockford, near Knoxville, and rented a house on a farm at $50 a month.

Random House published Outer Dark in 1968. Reviews were good, as they were for The Orchard Keeper, but sales were bad. Backed by the Guggenheim Fellowship for Creative Writing, he published Child of God in 1973. In between he renovated a barn on the farm – gathered all the stones, cut and kiln dried all the wood – adding a stone room and chimney.

In 1979 McCarthy published Suttree – a book two decades in the making – part love letter to his drinking days. He and DeLisle had divorced. He was living in a friend’s motel in Knoxville when there was a knock at the door. He’d been awarded the 1981 MacArthur Fellowship – a “Genius Grant”. He lived on the money while writing his masterpiece: Blood Meridian.

The Man and the Myth

Blood Meridian’s central characters – the Kid, Glanton, the Judge; the boy, the man, the force of nature – are three distinct iterations of McCarthy’s wanderer. They’re members of an outlaw gang marauding the wilds of the US-Mexico boarder, ostensibly collecting Apache scalps for which a Mexican governor has promised $100 apiece. They are united by their talent for violence: murderers, even by McCarthy’s standards, at their most indiscriminate.

But their enemies, too, turn bloodletting into an artform; Blood Meridian is not a simple revisionist western. Yes, the belief that the Anglo-Saxon race was destined to rule the continent of America, known as Manifest Destiny, is subverted. But more than this, in McCarthy’s mid-1800s violence is the norm. Life is cheap. The wind blows sand over bloodstains.

Many claim to be put off reading McCarthy for this reason: because his work is too violent. But the violence in his novels isn’t gratuitous. It’s not needlessly protracted, fetishised. And Child of God and Blood Meridian, at least, are based loosely on real events. This is the writer, meticulous in his research, calling it as he sees it – sharing “stories seen and heard tell of”. Longtime McCarthy scholar Dianne C. Luce puts it best: she said his “love of this dark world is a fire illuminating it.” Part of the reason McCarthy’s violence is tolerable is due to the language with which he lights the fire.

Which leads to another myth about McCarthy: that he is difficult to read. Blood Meridian isn’t by any means an easy read. Some sentences, paragraphs, whole pages require rereading. In all his books he uses little punctuation, no speech marks. But there are two sides to McCarthy. There’s the bard, biblical and byzantine… whose sentences run on and on and build rhythm and employ alliteration and repetition and refrain for emphasis and use obscure and arcane words to slow the speed and action to increase it again and amongst it all there will be a butchering so bloody or a sentence so beautiful it will take your breath away.

The other side of McCarthy is good at periodic sentences – sentences in which last comes the idea. He reports events in prose that’s simple and precise. One of the best examples being the standoff and shootout at the end of All the Pretty Horses or any of the set pieces in No Country for Old Men.

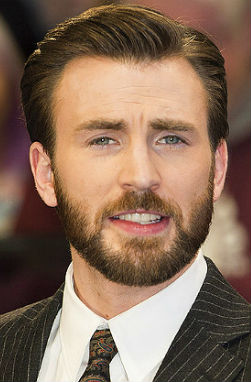

In the latter, a Vietnam vet takes money from the scene of a drug deal gone wrong. A World War II vet is the sheriff who no longer understands the world in which he tries to keep order. Anton Chigurh’s the killer with a captive bolt pistol, a thorn in both their sides, the greatest antagonist in modern literature. The action is described in such lean, exact terms that Joel and Ethan Coen, who turned the novel into an Oscar-winning film, joked that while adapting the story to script one typed while the other held open the book.

His Side of the Street

Blood Meridian’s release in 1985 marked a turning point for McCarthy in more ways than one. It was his first foray into the western – a genre he would leave scorched and blood-soaked and forever bearing his name. It was also his last book with Erskine. Partly as favour to his retiring editor – partly because he was promised he’d never need to do another – McCarthy gave the New York Times what was for a long time his only interview.

The interview and the work of new editor Gary Fisketjon brought McCarthy the wider audience his words deserved. The Border Trilogy – All the Pretty Horses (1992), The Crossing (1994), Cities of the Plain (1998) – each sold in their hundreds of thousands. Reviews glowed, more awards followed. He secured his place with the greats of American literature. With the money he made he bought a new pickup.

After No Country for Old Men (2005) came a novel inspired by a night in a motel with the son from his third marriage. As John McCarthy slept he looked out at El Paso and wondered what it might look like in 100 years time. Terrifying, he decided. The two pages he wrote that night later turned into an apocalyptic father-son adventure, The Road (2006).

To promote the book he appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show – presumably promised by whoever arranged the interview he’d definitely never have to do another. He was reticent but charming, looking younger than his 73 years. Asked why he’s so reluctant to speak to the press he said: “You work your side of the street, I’ll work mine.”

In 1997 McCarthy married third wife Jennifer Winkley. They divorced a decade later. He’s 81 now, and is writer in residence with the Santa Fe Institute. A convivial man, it’s said. He likes to spend time with the scientists. The New York Times interviewer called him a “gregarious recluse”.

His body of work currently stands at 10 novels. He’s written plays and screenplays and is happy to collaborate when doing so, which puts paid to another great myth – perhaps the greatest myth – surrounding the writer. Dr. Stacey Peebles is editor of the Cormac McCarthy Journal: “I do think that McCarthy has succeeded without working to ‘brand’ himself in the way that authors now are encouraged to do, though it’s also important to note that he’s not a true shunner of public attention – like Salinger or Pynchon. After all, he did appear on Oprah. He’d just rather be writing than talking about it. And he doesn’t want to interpret his work for you.”

This year he’s rumoured to be releasing his eleventh book, The Passenger – and is working on another two. Cormac McCarthy continues to work his side of the street and lets us, the reader, work ours. He believes the novel can “encompass all the various disciplines and interests of humanity”. We shouldn’t be surprised that someone who thinks so highly of his art, someone who works so hard at it, does not want to dispel the magic he makes by talking it away.

Perhaps his work could be easier to understand. Maybe he could use a little more punctuation. But why should an author who walks every road he writes, cocks every gun his characters shoot, give concessions on the page he refuses to make in life. You can grasp the meaning without completely comprehending the medium: his lies are to tell us some great truth about ourselves. He may prove one of the greatest writers of all time… He just isn’t in the writing business.

SHARES

Comments