She was reigning Miss World, lying on a hotel bed blanketed with money, awaiting another magnum of champagne. He was the greatest footballer of his generation, arguably of any generation, and he’d just relieved a casino of £15,000.

The night porter, delivering vintage bubbly to their room, was stunned by the intemperate picture Marjorie Wallace and George Best painted before him. Without so much as a hint of irony in his Irish brogue, he posed the now immortal question: “Mr Best, where did it all go wrong?”

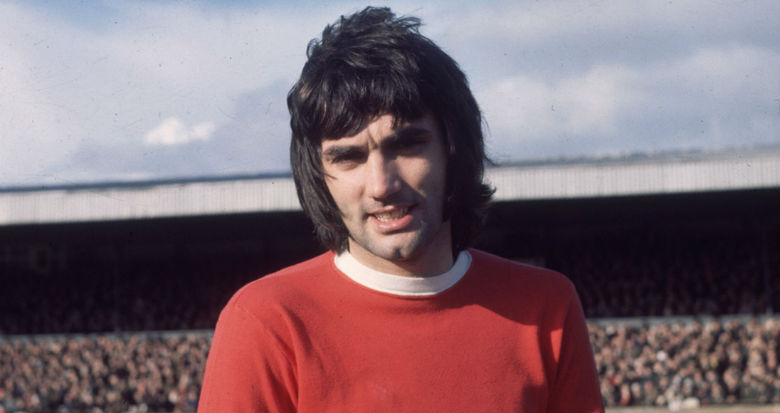

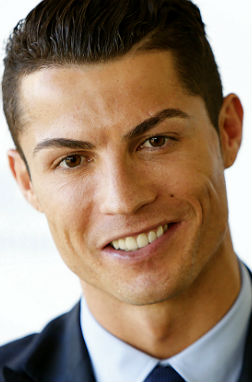

There was no precedent for Best. He was football’s first pop star. His every action scrutinised by an infatuated media. A player enamoured by the public as much for his antics off the pitch as he was for his abilities on it. But what abilities they were.

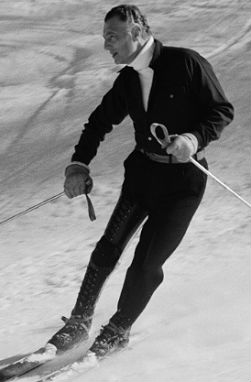

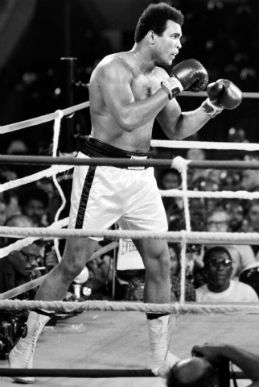

“Shellito was taken off suffering from twisted blood,” his Manchester United team-mate Pat Crerand once said after he tortured Chelsea full-back Ken Shellito. At just 5ft 8in tall and weighing just 10 stone in those early days, Best had an almost balletic poise, scything through defences like they weren’t even there.

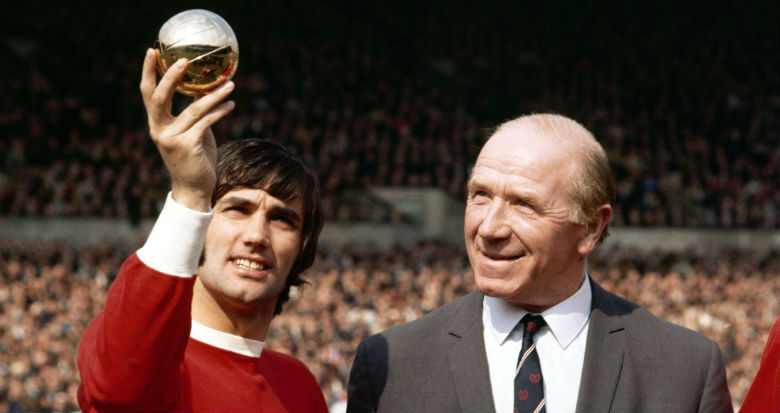

He was leading goalscorer for five consecutive seasons in an all-star United side, winning two league titles and one European Cup, the Ballon d’Or, Footballer of the Year and European Footballer of the Year – all by the age of 22.

In full flight, he was virtually untouchable, unplayable, leaving experienced opponents chasing shadows in his wake.

While Best’s star shone brighter than most, it ultimately burned out far too quickly He was a player that achieved only a fraction of what his prodigious talent promised. His career at the very top-level of football lasted only eight seasons, and the Northern Irishman never featured at a major international tournament.

Like Argentina’s Lionel Messi today, although under different circumstance, his inferiority at international level means critics often refrain from speaking about him in the same breath as Pele, Cruyff, Maradona and Zidane. Why, when so many arguments point to the contrary, should we recognise George Best as one of the greatest footballers of all-time?

Best was born in 1946, son of an iron-turner at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, the first of six children. He began kicking a football as soon a he could walk, learning the game on the streets and greens of the notorious Cregagh estate.

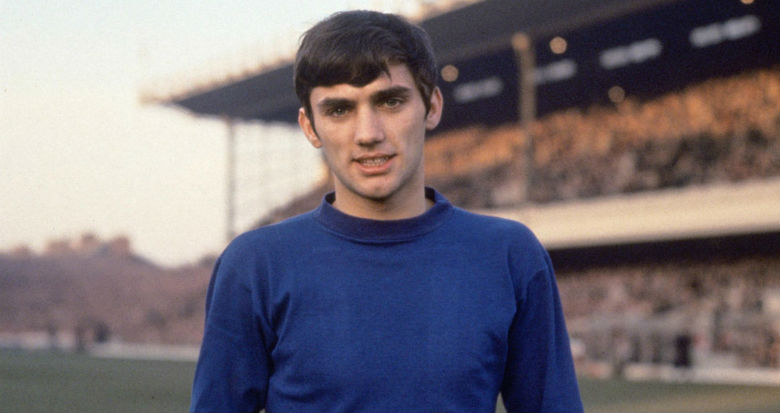

From a young age, it was clear the wiry and athletic Best was an exceptional sportsman. He was intelligent, too, passing his 11-plus exam and earning a place at the local grammar school – although his days at Grosvenor High School were notable for his achievements as a truant rather than an academic. Grosvenor was a rugby school, much to the dismay of the football-obsessed Best, and it had also separated him from his primary school friends, who attended the area’s secondary modern school.

“I have found a genius,” Manchester United scout Bob Bishop said in his telegram to manager Sir Matt Busby. Best had been transferred to Lisnasharragh Secondary, where he was reunited with both football and his friends, but failed to make the Northern Ireland Schoolboys team. He’d left school and qualified as a printer’s apprentice when Bishop saw him playing for the Cregagh Boys Club.

In 1961, two days into a two-week trial at Old Trafford, Best returned to Belfast. He was homesick. Busby, however, realising he had a precocious talent on his hands, persuaded him to return, where he went on to dazzle in United’s youth team.

A player with “style” and “natural talent” is how the Manchester Evening News described Best after his senior debut in 1963 against West Bromwich Albion, four months after signing a professional contract on his 17th birthday. Within a few months, he was a first team regular, playing with world-beating forwards Bobby Charlton and Denis Law, in one of the all-time great United sides also featuring Nobby Stiles, Paddy Crerand and David Herd. On a team sheet full of luminaries, Best began to stand out.

He started, nominally, on the wing but would roam at will and was a clinical finisher. In full flight, he was virtually untouchable, unplayable, leaving experienced opponents chasing shadows in his wake. He possessed a devastating mix of elegant skill and blistering pace, graceful balance and deft timing. He was brave, too. He had to be. What defenders couldn’t catch, they would invariably attempt to kick. And he saw it all through his innate gift for reading the game – a footballing brain that gave him the vision to see things others couldn’t, and the ability to do things they could only dream of.

Like all great players – with that essential selfish streak to their game – Best could also be exasperating, apparently taking on one defender too many or shooting from seemingly impossible angles. Such instances, however, usually resulted in yet another wonder goal.

In 1965, United won the league. The following year they reached the semi-finals of the European Cup, spanking the mighty Benfica 5-1 in the quarters, Best grabbing two goals in the opening 12 minutes. The league title was theirs again in 1967. Then, in 1968, a decade on from the Munich air disaster which killed eight United players, severely injuring manager Busby and captain Bobby Charlton, they were crowned European Cup winners, defeating Benfica 4-1 in a dream final at Wembley. Best was at the peak of his powers throughout.

“O Quinto Beatle” the Portuguese press labelled Best after his brace against Benfica in 1966. “The Fifth Beatle” moniker stuck with the British press, too. While he had all but reached his apex as player, his notoriety as a celebrity was still rising. During these years, he became more than just a footballer. His picture began appearing in mainstream magazines as often as it did in the sporting press.

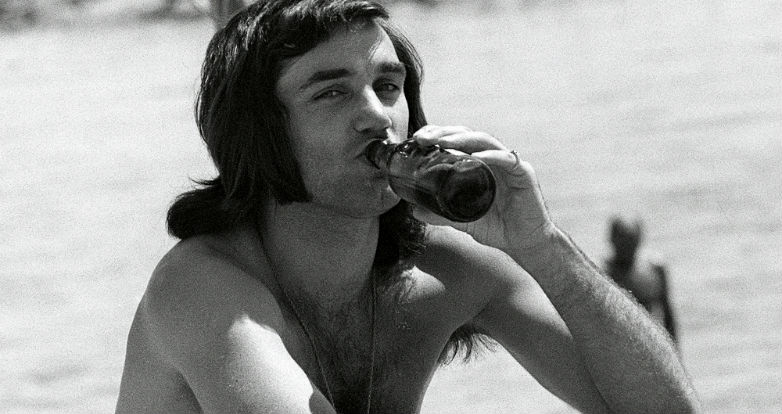

As the spotlight on him grew more and more intense, numerous commercial opportunities came his way – and with them, money, parties, girls and booze. Despite much forewarning from Busby, Best revelled in the limelight. “I was the one who took football off the back pages and put it on to page one,” he would later say.

His growing fame coincided with the decline of the great United side of ’68. It was an ageing team with an ageing manger that refused to part with the old guard and invest in new talent. Best, still relatively young, his individual performances often covering what was an increasingly average team, became frustrated at what he perceived as a lack of ambition at the club. The situation was exacerbated when Busby refused to make Best captain, due to his increasingly erratic behaviour off the pitch.

“By the time I was 25,” Best said. “I felt the team was in decline and alcohol was taking over. For three years I was out every night and gambling became a drug, too.”

During these years, Best got himself an agent and secretary, opening his own nightclubs and fashion boutiques. He custom-built a futuristic, largely glass new home in Bramhall – a goldfish bowl which seemed to invite the world’s gaze. His playboy lifestyle snowballed, as did the newspaper inches dedicated to lurid tales of his conquests. He would often return from delinquent lost weekends, drinking binges and missed training sessions, determined to make a fresh start. But it was too late.

Busby’s successors, Wilf McGuinness and Frank O’Farrell, also failed to control Best. Though he still turned in the odd majestic performance, his vices had firmly taken hold. He retired in 1972, but the then manager Tommy Docherty persuaded him to return. It was not to be a successful return. An overweight Best played his last game for United on New Year’s Day 1974. He was 27-years-old. That same year, United were relegated.

In the years that followed, he played, albeit briefly, for 11 different clubs – including Fulham, Hibernian and several American sides. Mere footnotes by comparison to his United years. From 1963-74, Best made a total of 470 appearances for United in all competitions, scoring 179 goals – including six in one game against Northampton Town in 1970.

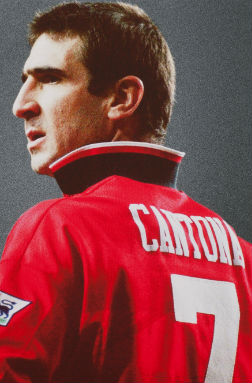

The arguments against Best’s legacy as one of the greatest footballers of all-time are many and varied. In a recent pole to find Manchester United’s best ever player, he finished third, behind Ryan Giggs and Eric Cantona. In researching this article, we came across a list of the world’s greatest players that omitted him even from the top 20. Cast a pragmatic eye over his career and this doesn’t seem so absurd.

His failure to play in the upper echelons of football for as long as he should have is striking, a longevity that’s present in almost all the greats. He never shone at a major international tournament – although he never got the chance to, winning 37 caps for Northern Ireland, his best efforts were not enough to galvanise a poor side. And, almost to the year, you can pinpoint the moment his self-destructive nature overwhelmed his intrinsic gift for the game – that moment, Mr Best, was where it all went wrong.

Football is more than simple facts and figures, more than a spreadsheet of appearances and goals, trophies and winners medals. George Best was the longhaired, champagne-swigging, defender-skinning, playboy embodiment of this belief.

He had all the attributes of a great: a flawless first touch, vision and extraordinary passing ability, brave in the tackle, a frightening change of pace and ruthless in front of goal. He also had rare virtues that elevated him from greatness to genius: intelligence, wit, imagination and style. Best was a born entertainer.

While he didn’t have the temperament to truly fulfil these abilities, he had something else. Something more. That intangible unknown that makes a working-class kid from Belfast idolised the world over. And, even after his death, through squandered talent, the alcohol, the gambling and the women, means he is still revered to this day.

He was a prototype footballer; a grave warning for all those who followed, a high-water mark they must all face by comparison. George Best: the greatest footballer that never was.

SHARES

Comments