Alfred Wertheimer recalls the exact date he received the phone call that would lead to his first meeting with Elvis Presley. “March 10, 1956,” he says, speaking from his home in New York. “I was a freelance photographer, 26 years old, and I had taken a call from the public relations department at RCA Victor Records, asking if I was available the following week to go to Studio 50 in Manhattan, one of the CBS Studios, where they were filming Stage Show, hosted by the Dorsey Brothers. I said, ‘Sure, Tommy Dorsey is one of my idols,’ but she explained that wasn’t what the job was for.”

Stage Show was a popular music variety series, and the Dorsey Brothers were big band leaders. The reason RCA wanted Wertheimer to visit the set was to photograph an artist who had recently signed to the label, and who would be performing – prompting him to ask a question that would probably never be asked again. “She said to me, ‘I want you to cover Elvis Presley,’” Wertheimer recalls. “There was a brief silence, and I said, ‘Elvis who?’”

Related:

Rock stars who were seriously rocking

Violence and adultery: the dark side of John Lennon

Keith Moon: the most explosive rock star in history

At that time, Elvis Presley was just 21 years old and in the early stages of his career. He had signed to Sun Records, based in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1954, and had already built up a small fanbase by the time he moved to RCA in November 1955. Wertheimer was about to meet him two months after his first RCA single, Heartbreak Hotel, had been a massive number-one hit, and just over a week before the release of his self-titled debut album – an artist on the brink of superstardom.

But turning up for that first meeting, Wertheimer could not have imagined anyone more relaxed and laid back. “It was St Patrick’s Day, March 17, and someone met me at the stage door,” he says. “They led me past the other musicians and into a back room, where I see a young man of about 21 and a middle-aged man. The lady who met me walked up to the younger man and said, ‘Elvis, I’d like you to meet Alfred Wertheimer. He’ll be taking some pictures, is that OK with you?’ And he didn’t even look up, he had one foot up on the table, I could see his Argyle socks reflecting in the mirror, and he said it was fine. I then realised the other guy was a jewellery salesman, who had delivered a ring to Elvis, and he was distracted by it. I took out my cameras, and that was my first real job.”

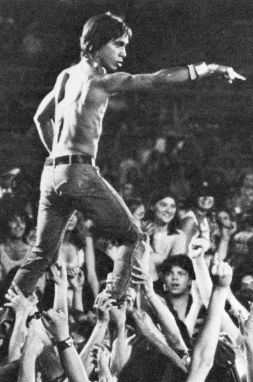

It wasn’t long after the salesman left that Elvis took to the stage for his performance. As he launched into two of his songs, Wertheimer got a glimpse of the star power that would soon see the rest of the world transfixed. “He got quite a reaction from the young ladies,” he recalls. “They were so loud, you could barely hear the songs. And something he did that was different, he made them cry. Yes, you can make the girls scream, jump up and down, but crying is a very deep emotion, and anyone who can do that is a very powerful entertainer.”

It was something that Wertheimer would see more of, as the young photographer was asked to meet Elvis again a few months later – during the recording sessions of Don’t Be Cruel and Hound Dog, and on tour, playing other venues around the States.

A collection of the images from this time can now be viewed in Wertheimer’s book, Elvis and the Birth or Rock and Roll, published by Taschen. He describes the photography style as ‘fly on the wall’, where he would try his best not to draw attention, not even using a flash and often shooting with his camera at chest height, so that his subjects did not realise he was taking pictures.

This intent on being an observer meant he never really became close to Elvis, despite the two spending a lot of time together. “I didn’t want to become his buddy,” he confirms. “You need to keep your objectivity, so I backed off a little. I remember one time he asked my advice, we were in a clothes store and he held up a shirt and said, ‘Al, what do you think?’ I just said to him, ‘Do you see the way I’m dressed? Do you really want to ask me for fashion advice?’”

But while Elvis’s popularity was growing, Wertheimer reveals that his record label still needed convincing during those early days. “RCA weren’t so confident that he would become as well known as he did,” he says. “They said to me, ‘Al, don’t shoot colour because we’re not going to pay for it. Right now, he’s doing OK, but we’ve seen this before, so you never know, and we don’t have the budget for colour.’ I still shot some colour though, as my incentive was the freelancing, and I could try to sell those for magazine covers.”

If proof of Elvis’s popularity were needed, however, it came in the amount of fan mail he was receiving – which seemed to prompt an unexpected reaction. “In his hotel, Elvis dropped himself on the couch and opened a manila envelope,” Wertheimer reveals. “And there were perhaps 100 fan letters. He started reading some, and when he finished, even if they were six or seven pages long, he would tear them up. I asked him why, and he said, ‘Well, I’ve been carrying these with me, and since it’s my mail I don’t want anyone else to read them. I’d rather destroy them than leave them lying around.” And I was like, how can you destroy your fan mail?”

It may have seemed odd, but over time it became something Wertheimer called ‘Elvis logic’ – things that made sense only to him. Wertheimer recalls an example of this in an interview, when Elvis was asked about his constant gyrating on stage. “Don’t you think you’re being rude, thrusting your hips?” the interviewer said. But Elvis replied, “No, that’s the way I sing, I sing with my whole body.”

But whatever the situation, Wertheimer always found Elvis a joy to photograph. “He wouldn’t flinch when a photographer got close, and I mean close, just a few feet away,” he says. “A lot of people get nervous, but he was totally oblivious.”

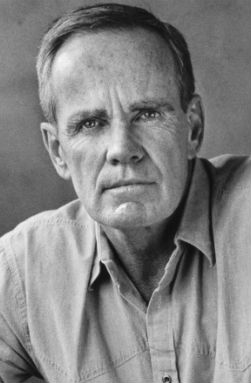

The man behind the lens: Alfred Wertheimer poses in front of his famous Elvis photographs.

After the events of 1956, however, the two would only meet one more time, on September 22, 1958, when Elvis had joined the army and was preparing to sail to Germany. “His mother had died the year before, his sideburns had gone, and that bushy hair had been replaced with a crew cut,” Wertheimer reveals.

Yet while they would not cross paths again, Wertheimer had accumulated more than 3,000 photos of Elvis, with work that defined his career. “I’m still trying to show that I’ve shot other people,” he admits. “Time magazine just did a story with photos I took of Nina Simone, but Elvis let me have access. Things got tighter as he got bigger and moved to Hollywood, so it was a special time.”

And just as he remembers the date that started it all, Wertheimer remembers another only too well – August 17, 1977. “For 19 years, I never got a single phone call from anyone wanting a photo of him,” he says. “From the day he died, it hasn’t stopped.”

But Elvis was always an admirer of photography, and would surely not object to living on in Wertheimer’s work. “When we were in that clothes shop, by the dressing room, the owner had seven or eight framed photographs of performers he had been given,” Wertheimer recalls. “Elvis stopped and looked at them, almost as if to say, ‘One day, I’ll have my photo on this wall.’”

Details: Alfred Wertheimer: Elvis and the Birth of Rock and Roll is published by Taschen, AED 2,500, limited to 1,956 copies. See taschen.com. Images: © Alfred Wertheimer.

SHARES

Comments