The year is 1994 when in his rearview mirror Jay Z spots the long arm of the law. Narcotics concealed in his trunk, he faces something of a dichotomy: does he flee or pull over?

Fleeing would provide an independent basis for chasing and arresting me, he thinks,which would inevitably result in the car being impounded and the contrabandfound. The inadequacies of the suspicion supporting this initial attempt at seizing the substances would not mitigate their discovery, should there be an intervening attempt at escape. No. Jay Z decides he’s in no mood for a highway chase. He’s relatively wealthy; should the case end up in court, he could afford pretty decent legal representation.

The New Jersey police officer asks Jay Z to step out of the car, insinuating, simply because he’s African-American, he may be carrying a concealed weapon. Jay Z politely declines the offer. The car isn’t stolen. All paperwork is present and correct. He’d prefer to remain where he is, thank you.

In that case, the policeman would like to look around the car. Jay Z advises him that both trunk and glove compartment are locked, and while he concedes his knowledge of the law is limited, to search them the officer requires a warrant. The policemen is somewhat startled by this. He knows, in fact, he does not require a warrant to search the vehicle. He does, however, need either consent from Jay Z or probable cause. He has neither.

The officer, clutching at straws, suggests Jay Z would not be so cocksure if a drug-sniffing dog was present. Jay Z senses victory. A drug-sniffing dog is not present and the policemen has no right to detain him until one arrives. I have 99 problems, Jay Z finally says to the officer, but a female drug-sniffing dog is not one.

Shawn Corey Carter requires just two verses to prove himself not only perceptive on points of law, but able to succinctly articulate his – and perhaps hip-hop’s – obsession with wealth. The verse preceding the one above requires little interpretation: “Rap critics that say he’s Money, Cash, Hoes / I’m from the hood, stupid, what type of facts are those / If you grew up with holes in your zapatos / You’d celebrate the minute you was having dough.”

The juxtaposition of the two verses, from 99 Problems (2004), serve as autobiography and rationale, as motive and means: critics have not walked in Jay Z’s shoes – the ones with holes in them, metaphorical or otherwise. He grew up in some of Brooklyn’s poorest housing projects. As a child, visited neighbours to eat when there was no food at home. One friend pointed him in the direction of drug dealing; another later convinced him to focus on music – though his dodging three shots of an assassin’s gun helped, the weapon jamming on the fourth attempt.

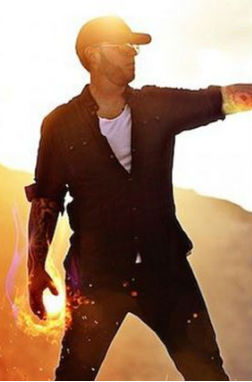

Once music became Jay Z’s singular focus he proved himself motivated, ambitious, ruthless. He found mentors, learned all he could from them – and often dispensed with them once he’d done so. If his poetry brought him acclaim and more than enough money to live comfortably, his business acumen brought him wider respect and untold riches.

Instead of rapping about his favourite brands, he founded and rapped about his own: in 2007, he sold clothing label, Rocawear, for over AED 730 million. A year later he struck a AED 550 million deal with event company Live Nation. He’s currently earning a healthy income from his record label, sports agency and management firm Roc Nation.

That’s just part of his portfolio. So shrewd an entrepreneur is Jay Z, in fact, Forbes’ Zack O’Malley Greenburg was compelled to write a business-focused biography of the rapper: Empire State of Mind: How Jay Z Went from Street Corner to Corner Office.

Greenburg calls his story “the American dream in its purest form.” But when the journalist asked for an interview, Jay Z declined. There was no money in it. Whether it was already in the pipeline or not, Jay Z beat Greenberg to the punch with his own book, Decoded. It became a bestseller.

“We see a lot of things going on with our young people,” former Source editor Bakari Kitwana said in a recent interview, “and we don’t feel like we are teaching them values that can compete with the way the value of money is ingrained in our culture. Everything is just focused on money. If you can get money, whatever else you’re doing doesn’t matter. It’s reached a crisis point. I came up in the 1970s and 1980s, and greed has always been present, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen it like it is now.”

DR BEATS

With an estimated wealth of $520 million (AED 1.9 billion), Jay Z manages just third place in the recent Forbes Five: Hip-Hop’s Wealthiest Artists 2014. Sitting atop Forbes’ list is Andre Romelle Young (AKA Dr Dre), thanks to Apple’s recent acquisition of Dr Dre’s Beats Electronics LLC in a $3 billion (AED 11 billion) deal. It’s estimated that the deal increased his personal fortune to around $800 million (AED 2.9 billion).

As part of World Class Wreckin’ Cru and N.W.A, as solo artist and collaborator, in front of the mic and behind the mixing desk, Dre has spearhead some of hip-hop’s most seminal moments. Over a quarter- century-long career his eye for talent and skills in the studio have launched the careers of Snoop Dogg, Eminem, 50 Cent and Kendrick Lamar, and he’s cited as an influence by everyone from Kanye West to Arctic Monkeys.

But money made from music – at least his own sales – makes up a relatively small part of his fortune. It’s the sale of Beats, the headphones and music streaming company Dre co-founded with Interscope Records’s Jimmy Iovine in 2008, that is responsible for rocketing him to the top of the Forbes Five. The company controls two-thirds of the premium headphone market, with annual sales of reportedly $1 billion and rising.

Positioned as premium headphones, it’s argued that compared to its competitors, they offer superior sound quality at a significantly superior price. But, then, the brand almost single-handedly popularised “premium headphones.” Beats is a lesson in shrewd marketing, product placement and celebrity endorsement. It ensured success even Dre couldn’t have anticipated.

With Dre, it’s difficult to separate the persona from the person: “I’ve looked at pictures that my mom has of me,” he previously told a magazine, “from when I was four years old at the turntable. I’m there, reaching up to play the records. I feel like I was bred to do what I do. I’ve been into music, and listening to music and critiquing it my whole life.” In another interview he said: “Once it comes out, for me, it’s just business. Numbers.”

Dan Charnas, author of The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop, says Dre’s business nous stems from hip- hop’s intrinsically entrepreneurial nature. “There’s a long tradition,” he told the BBC, “of entrepreneurship for artists in the hip-hop business because there was no other way they were going to get out there.” In rap’s early days, major labels and radio stations were reluctant to push the genre. Its artists had to be creative – start their own labels, market their own music. “The hustle of that,” Charnas says, “extended to everything.”

DIDDY FIGHTS BACKS

The race to be hip-hop’s wealthiest player is not yet won. The Cash Money Records co-founders also make the Forbes Five, brothers Bryan “Birdman” and Ronald “Slim” Williams having a combined net worth of over $300m (AED 1.1 billion). The label makes money from artists Drake, Nicki Minaj and Lil Wayne, and from Cash Money Content, GT Vodka and the YMCMB clothing brand.

Propping up the list with an estimated $140m (AED 360 million) is 50 Cent. Named Curtis James Jackson III, he made most of his money from the 2007 sale of the drink Vitaminwater. He is currently trying to repeat that success with SK Energy beverages and mirror Dre’s windfall with SMS Audio, and also by running his now independent imprint G-Unit Records.

Sean Combs – who is now back to his original moniker of Puff Daddy – has been hip-hop’s leading money man for the past decade. He packs an estimated fortune of $700 million (AED 2.5 billion) – banking a $120 million (AED 440 million) net worth last year alone. Revolt TV, a new multi-platform music channel, is the latest addition to an already sizeable portfolio which includes a vodka brand, restaurants and clothing lines.

Dre may have unseated Diddy with the Beats deal, but Revolt TV could see him quickly regain the throne. The channel encourages user participation, and claims from its crowd-sourced content a “royalty- free, non-exclusive, perpetual, unrestricted, worldwide license” to publish material. The logistics of the model have yet to be finalised, but whether it’s fair for contributors or not, it is a cheap way to established the brand with a view to moving into more expensive original programming. And Combs rarely passes on an opportunity to expand.

If Bakari Kitwana’s right and our society has become obsessed with money, hip-hop is not just a reflection of that fact, it also condones and perpetuates it. It’s a sweeping generalisation to say all rapper’s value lucre over lyrics. But, then, those standing on the biggest stage have the best tools for change.

Because Dan Charnas is also right: the entrepreneurial spirit is central to hip-hop culture. Jay Z, Dr Dre, Puff Daddy: their prodigious musical talents outstripped only by discipline, dedication, doggedness. These are self-made men, artists with business brains, overcoming seemingly insurmountable adversity to redefine the American dream. For such visionaries, ones who have the world’s ear, it seems myopic to promote success’s ends rather than its means.

SHARES

Comments