The first time the cops raided Studio 54, Scott Taylor thought it was a joke. December 14, 1978. A Saturday night. Taylor was working the bar when 40 firemen burst through the front door. Studio was home to rollerskating fairies and sequined clowns: firefighters were relatively dull. “Oh look, there’s another load dressed as police, that’s funny,” Taylor remarked shortly afterwards. Then the lights went up.

Studio had been busted. Cops tore the place open. Liquor licences hadn’t been granted. Logbooks recorded ‘party favours’ dished out to punters. Bags of cash – $600,000 of it – were stuffed in the basement ceiling. The club had paid $7,000 tax the year before. By 1980 Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, two Brooklyn boys who’d turned an old opera house into the world’s most famous nightclub, were in jail and their club was shut.

Related:

Hollywood’s most scandalous hotel - Chateau Marmont

Violence and adultery: the dark side of John Lennon

Keith Moon: The most explosive rock star in history

Both men would eventually seek – and reap – even greater wealth. Even Studio would reopen in 1981 for an extended swansong. But few would argue it ever reached the highs it had during 20 months in which it took a city on its knees by storm, and flipped the opaqueness of celebrity full-circle.

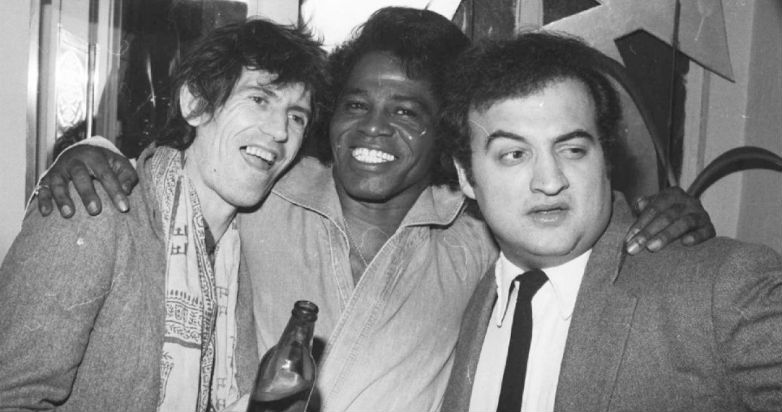

Studo 54 co-owner Steve Rubell, right, talking to reporters after leaving court.

It may barely have been nine years old when the disco ball finally stopped turning in 1986, but Studio 54 had racked up as many stories as the raconteurs who crossed its famous velvet rope. “It’s the place where my prediction from the 60s finally came true,” remarked Andy Warhol. “In the future everyone will be famous for 15 minutes.”

Fifteen minutes were more than anyone bet Studio would last, at the beginning. Schrager, the son of a factory owner from the quiet suburb of East Flatbush, seemed every bit the budding entrepreneur when he met Steve Rubell at university. Schrager was on his way to qualifying as a lawyer while Rubell failed at dentistry, before switching to finance and history.

The two young men could hardly have been more different: Schrager, the quiet, consummate pro and Rubell, the scruffy, goofish loudmouth whose outspoken honesty was often interpreted as obnoxiousness – usually correctly. Even during Studio’s most successful times, when Rubell was dancing with the stars and sleeping on $100 bills, one New York magazine reporter wrote that: “he looks and dresses like a slob.”

“Steve was the gregarious one who would bring in guys to make deals with and Ian would be the dealmaker,” says Scott Taylor, then a skinny 19-year-old bartender who followed Schrager and Rubell from their first club, a chintzy spot called The Enchanted Garden, in 1975. That venue, an 11-room mansion in Queens, was famous for its themed nights – “Islands of Paradise” with hula dancers and palm trees; “Arabian Nights” with llamas, camels and a snake-charmer – until yuppie locals complained about the noise and shut it down.

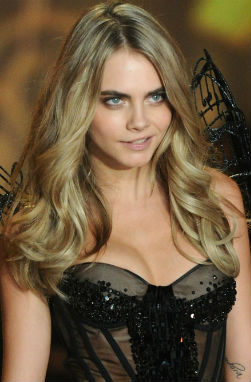

Bianca jagger riding a horse through Studio 54.

Soon, though, the pair were eyeing a spot in Manhattan. After all: who thought of New York as leafy Queens? They needed to be at the heart of the city, and a former opera house and recording studio just off Broadway on 54th Street looked the part. Rubell and Schrager wasted little time: in just six weeks the pair, alongside financial backer Jack Dushey, had transformed the old building into a cavernous player on the city’s club scene with a $400,000 outlay. “I wanted an old theatre,” said Rubell at the time, because he wanted “a place big enough for a circus.”

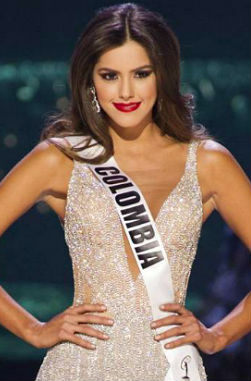

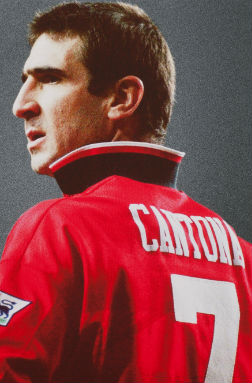

A circus it was. Lavish parties were arranged by Peruvian PR guru Carmen D’Alessio, like the one where Bianca Jagger rode in on a white horse or when Armani was treated to a drag-ballet act. Rubell loved to see local schmoes shimming alongside megastars on the dance floor – ‘mixing the salad’, as he called it. “Outside everybody was separated,” says Taylor. “But if you got in, whether you were Elizabeth Taylor or you were a gas station attendant from Newark who was young and cute, you were all equal once you got in.”

Of course that wasn’t quite true. For while Rubell stood outside with head doorman Mark Benecke, strutting back and forth and picking who could dance and who could go home (he took particular joy in refusing entry to “f**king rich guys” who thought that waving a few dollars about would get them past the rope), inside the stars often made the show.

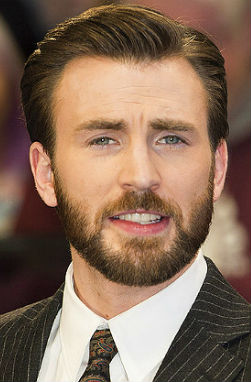

Celebrities flocked to Studio 54 in droves and drew astonished glances wherever they danced, drank or enjoyed some of the $80 ‘favours’ Rubell and Schrager dished out by the gram. Calvin Klein and Brooke Shields shimmied up to the DJ booth suggesting tunes, while Andy Warhol glided from person to person, camera in hand and Truman Capote peered out from the nosebleeds at busboys half-dressed in leather. “It was the preliminary tremor of a social upheaval that would prove much more enduring than the populist revolution of the Sixties: the coming of the Celebrity Culture,” said writer and Studio regular Anthony Haden-Guest.

Andy Warhol.

But it was just as much the freaks, the weirdos, and those who just didn’t fit in anywhere else, who made Studio such a cultural wonder. America was a conservative place: Flower Power had faded in Altamont with the Stones, a generation was dying in ’Nam and Watergate had exposed the rot from within Washington.

New York itself was a mess: decrepit, drug-addled and so broke even the President told it to ‘drop dead’ in ’75. Hypodermics lay strewn and red lights shone out across Time Square. Graffiti and arson crushed entire Bronx blocks. Gangs roamed streets police didn’t dare tread (inspiring cult 1979 classic The Warriors). A blackout in ’77 led to widespread looting and violence. “I see kids walking around in flip-flops now,” says Taylor, “and I think: ‘how the f**k you gonna run?’”

New York was dirty, dangerous and destitute. But disco, a new electronic opiate, offered sweaty anonymity to those who couldn’t spread their wings elsewhere. “The famous people came to see the freaks,” says Taylor. The old white man in the tutu and rollerskates; the black woman in a NASA suit; the Rasta in Tibetan boots: “Studio 54 was this unbelievable island where nothing mattered more than feeling good,” says Fox anchor Geraldo Rivera.

“[Studio 54]‘s where you wanna come if you wanna escape,” said a young, gifted and (then) black Michael Jackson, and to some extent this was true: there was no Twitter, no Facebook, smartphones or web chatter outing outrageous behaviour which very frequently occurred – although Taylor claims Studio’s crazier aspects must be put in context: “Everyone did bad stuff, but no-one knew it was bad for them then,” he says. “Nothing seems quite so hedonistic as it does now.”

A young Michael Jackson.

Some might beg to differ: about the ‘rubber room’, for example, where you could be sure to find at least a couple of people cavorting to the beat, or about the chemical assistance almost everyone employed. Not least Rubell, who would often be the last to leave at 6am, eyes wide shut and muttering wired nothings to men he’d just met.

Studio was soon taking in $600,000 a month, mostly in cash. Rubell, New York’s mad new millionaire, had been taking $75-a-week unemployment cheques just six years before. Now he was palling up with the hoi polloi every night. By the time he was telling national radio that “what the IRS (Internal Revenue Service) doesn’t know won’t hurt them,” and that only the Mafia was making better profits than Studio 54, it was only a matter of time before the cops acted. Rubell was rumoured to be worth between $12m and $15m in 1977. A judge found them guilty of evading $800,000 in tax, sentencing them to three-and-a-half years each. That was reduced to 13 months after Rubell and Schrager turned disco-snitches, spilling the beans on every club owner in town.

Studio 54 would reopen in 1981 under new owner Mark Fleischman. And sure, the Warhols, Jaggers and Kleins still strolled through its doors. But it was the 80s. Greed ruled: Schrager and Rubell had proved it. And while the freaks still frittered past Benecke’s velvet rope, and the Schmoes and stars still danced till the early hours, the magic had somehow left. “I think that Studio 54 brought this legacy of greed, where the owners would swim around in piles of money,” admits Mark Christopher, adding that another terror was just around the corner. “For the moment Studio really opened things up: sexuality, freedom. But that led to the AIDS crisis, which became so devastating immediately afterwards.”

Bianca and Mick Jagger.

By the time Studio finally shut its doors in 1986, the communities who’d finally been able to express themselves in the club were under siege from the media and the deadly disease. Schrager and Rubell, for their part, bounced back from prison to own a host of trendy hotels in New York worth hundreds of millions of dollars, stuffing their new-found wealth into pioneering real estate rather than old garbage bags.

Rubell, who himself contracted AIDS, would die in 1989 aged just 45, of complications from hepatitis and septic shock. “I’ll never get over that,” Schrager told New York in 2007. “I’ll never have that kind of friend.”

Schrager has since opened more hotels under his eponymous company, working with high-profile collaborators like artist and director Julian Schnabel. But he knows that those 20 months in which he and Rubell created something truly unique, will be his ultimate legacy: “I’ve been doing things for 30 years, but when I die and there is an obituary, they’re going to talk about Studio 54. And I guess there is nothing I can do about that.”

SHARES

Comments