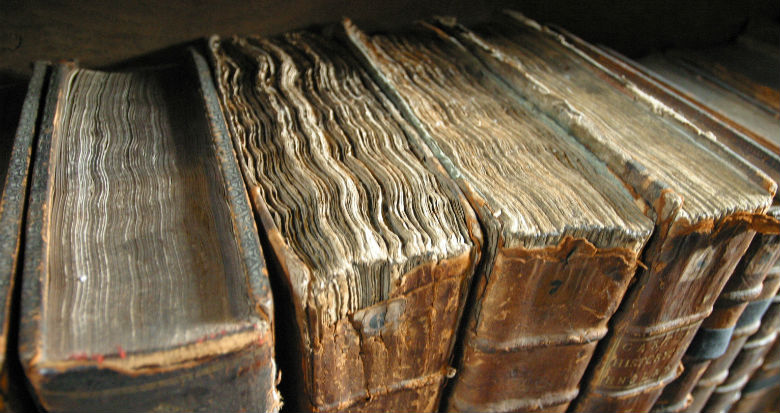

On the outskirts of Bucharest sits a military compound containing more than two million files. Bundled, browning, stacked floor to ceiling, these files cover 20km of shelves and 50 years of surveillance, the work of the secret police that enforced Romania’s communist regime. It’s known as the Library of Evil.

The secret police, the Securitate, would open a file on citizens for seemingly arbitrary reasons: family abroad, spoke a foreign language, overheard telling jokes… At its peak it employed more than 10,000 agents. One in three Romanians were informers; some as young as 10.

Romanian dissident and writer Vasile Gavrilescu was an old man when, in 2001, he finally gained access to his file. During the half-century communists controlled Romania, he served two terms in prison, watched on as his wife received a 12-year sentence, missed the birth of his daughter, spent his entire adult life either running from or under surveillance by the Securitate, and was eventually forced into exile. But even he, stepping off the train at București Gara de Nord one brisk May morning, making his way out to Dragoslavele Street, to the National Center for the Study of Securitate Archives (CNSAS), could not have conceived of the evils the library held for him.

Related:

The world’s coolest conman: Christophe Rocancourt

The Cult of Pablo Escobar, the ruthless Mexican drug lord

“Surviving the Titanic ruined my life”

Here a young clerk led him to a reading room where he found the Securitate kept on him not a file but 22,000 pages of detailed surveillance, a great tome that led Gavrilescu as a voyeur page by page through his past. And at the heart of it all sat the key that unlocked the mystery of exactly how the Securitate managed to infiltrate his life so completely. “I was,” he later said, “like a fish in an aquarium.”

The young rebel

Gavrilescu’s mother gave birth to him in a field. She worked in a factory and when her employer found out she was pregnant, he fired her. She couldn’t afford to pay rent and was forced to leave her flat. He never knew his father.

The boy bounced around several military and state schools, a schooling that would ultimately define the man. At seven years old, Gavrilescu was part of the copil de trupă – the Royal Army’s military unit for orphans. He enjoyed his time here. In 1948 the government, controlled by the Communist Party of Romania, controlled by Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, forced King Michael at gunpoint to abdicate. When the 10-year-old Gavrilescu heard the news he shot himself in the heart.

But the bullet narrowly missed and doctors managed to save him. At 14 he sat and passed a naval exam in the southeastern port city of Constanţa, but quickly fell out of favour with his superiors, who told him he would never make it as a communist military man and kicked him out. Gavrilescu returned to high school in Craiova, where he met his future wife, Aurora.

Aurora was blonde, beautiful, two years his junior. She liked to listen to Gavrilescu talk, and Gavrilescu loved to talk. They met in 1955 and married in 1958. In between, in 1956, they watched Hungarians rise up against Soviet control and its own secret police. Its people installed their own government and pledged to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact which tied it to the Soviet Union. Soviet troops ultimately responded with a brutal show of force. The revolution lasted little more than a couple of weeks, but now all Gavrilescu’s talk was about leading Romania’s very own revolt.

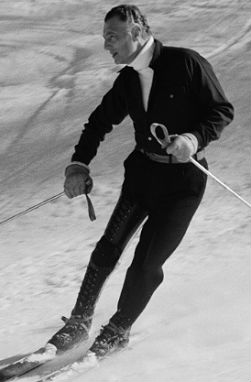

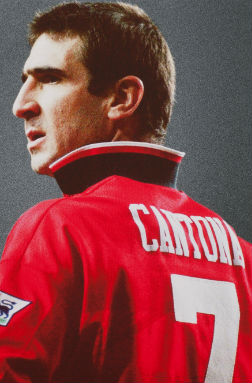

The 1956 Hungarian Revolution was ended with a swift show of force from the the Soviets.

He believed he could gain American support for his revolution and so formed an underground paramilitary group with the aim of overthrowing the government. “With my 18 comrades,” he said, “we had planned to take up arms and seize strategic points around the city.”

Gavrilescu’s revolution never really got going. The Americans didn’t come. And in increasingly strained circumstances, with the Securitate and its network of informers casting a long shadow over every aspect of life in Romania, his group lost its appetite for insurrection. Gavrilescu had long since suspected there was a rat in his ranks, and when it was clear his revolt had failed, he and Aurora had no choice but to flee.

He was right to do so. The Securitate came to Craiova looking for Gavrilescu, by which time he and Aurora had fled west, first by train and then on foot. They took guns, provisions. Gavrilescu had previously made round-trips to Yugoslavia to seek financial support for his resistance, so was confident he could get them across the border. But doing so meant waiting for the right moment to sneak past patrolling guards. So they waited. They waited and waited and when, finally, under the cover of darkness they decided to cross, the couple successfully avoided the attention of the guards; but not the noses of the guard dogs. The dogs began to bark. Gavrilescu and Aurora hid in a bush but when they heard the thud of the hooves of the mounted guard’s horses, Aurora panicked and fired a shot. The guards found the couple and returned them to Craiova and the Securitate.

During communist rule it’s estimated 10,000 Romanians were executed without trial. Gavrilescu and Aurora did, after several months, stand trial, but there was only ever going to be one outcome. He pleaded with the court to be tried and punished alone, to no avail. Aurora received a 12-year term. In deciding Gavrilescu’s sentence, the judge asked how old he was. When he replied “22″, the judge said, “Well, we’ll give you 22 years.”

“It wasn’t just physical oppression,” Gavrilescu says of his time in prison, “but also the abolition of human rights. I received a canteen of dirt every three days. I had to eat on my knees, hands and feet chained. And then they would come and kick you and take away the canteen: ‘You’ve had enough.’”

But prison also gave Gavrilescu the opportunity to learn new ways to fight the system: “I had the opportunity to receive a good education in prison, with ministers, aristocrats, intellectuals, people from the Sorbonne and Oxford.” He’d served five years hard labour when Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej’s government issued a decree of amnesty for political prisoners. Aurora left prison in June of that year, Gavrilescu in August.

On the train home Gavrilescu recalls feeling great remorse at having ever involved Aurora. When he found his wife, living with her brother, he remembers feeling prison had caused a change between them.

The log arm of the Securitate

After World War II, a pro-Soviet government took control of Romania, a former Axis member. The government included members of the Communist Party, gradually increasing in number until King Michael’s abdication confirmed their superiority. Nicolae Ceaușescu became head of the party in 1965 and ruled under various titles for more than two decades. Ceaușescu was – at first, at least – popular with the people. But Gavrilescu was never convinced.

He and Aurora were giving their marriage another go, Gavrilescu working as an electrician, but recalls feeling his wife grew more distant as the officers of the Securitate circled ever closer. “It’ll be worse now that Ceausescu is in power,” he told Auroa. Gavrilescu had spoken directly with the Yugoslav authorities, which had agreed to offer him political asylum, as they had many of his fellow Romanians.

Gavrilescu had been lifting weights for one year, steeling himself to swim Europe’s second biggest river. In the dead of night he dove into the Danube’s icy waters and beat a path to the banks on the Yugoslav side. He was free from prison but couldn’t escape the Securitate. His only choice, he felt, was to seek asylum in Yugoslavia, and send for his wife once he was there.

The icy river Danube.

He survived the swim across the Danube and made it through Yugoslavia to the coast but found there that Ceausescu had cut a deal with president Josip Broz Tito. Officers arrested Gavrilescu and returned him to the Securitate, Romanian authorities trading in return two tonnes of salt. He received a seven-year prison sentence; he served three and half, during which time he’d missed his daughter’s birth. She was walking and talking by the time he saw her.

It was around this time Gavrilescu began to write. He was again working as an electrician and was again under surveillance by the Securitate. He would put his books and papers in his electrician’s bag and cover them with tools. He recalls how sometimes it would take hours of walking to loose his tail. His sanctuary was Craiova’s cemetery. Here among the candles burned-out and flowers wilting he recalls how, occasionally, he would break down and cry. But mostly he would puff on his pipe and read and write. He wrote poems and prose, fictional and autobiographical. He wrote about his time in prison, the people he met. He wrote overtly and allegorically about those who enforced the regime and those who suffered at their hands.

The problem he had was never in the writing – most of which he’d written in prison in his head many times over – but working out where to hide his work. He built dressing tables with a double bottom in which he could conceal his manuscripts. Gavrilescu, now, had no one he could trust – no comrade or colleague or neighbour. So he told no one but Aurora.

Gavrilescu in total published 17 works. It would have been 21 were it not for the November 1972 raid on his apartment. Officers claimed they’d received an anonymous tip-off he’d been smuggling diamonds, but after entering his home headed straight for the doubled-bottomed dressing table in which Gavrilescu had four completed manuscripts.

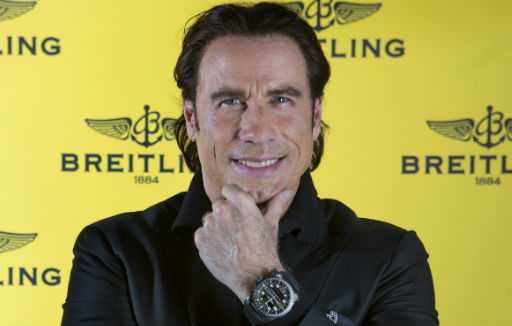

Nicolae Ceausescu at a communist rally.

In bed with the Securitate

When the young library clerk brought the old writer a glass of water and asked him if his file had been of any use, he saw in Gavrilescu a man changed. In total more than 40 people had collaborated with the Securitate against him. There was no aspect of his life which wasn’t scrutinised – the Securitate had informers in his resistance group, in his employers, in his neighbours… The Securitate also made an informer of his most trusted ally: his wife.

“I Aurora Gavrilescu,” one page read, “today sentenced to 12 years in prison, hereby undertake to cooperate absolutely with secret state security bodies and inform them in advance of any hostile action against the democratic regime staged by prisoners with whom I come into contact, with no exception, including close or distant relatives.”

Not only had Aurora flipped, working for the Securitate for most of her marriage to Gavrilescu, but there was also a suggestion she was having an affair with a high-ranking Securitate officer. It was Aurora who told the Securitate that Gavrilescu was writing “deeply hostile, even revolting” material and would be “happy to speak on Radio Free Europe in order to defame and denigrate the achievements of our country.” She helped the Securitate bug their apartment, the detail in the planning of which is incredible.

The Securitate organised a mock compulsory meeting for Gavrilescu’s apartment block so all his neighbours, including those elderly and house-bound, would leave their homes. Two officers stood guard to prevent anyone entering the building. It took two hours to install cameras and microphones, and as this required lots of drilling, the officers played a radio loudly to conceal the noise.

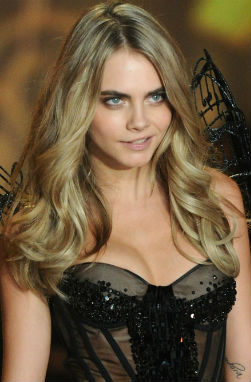

Vasile Gavrilescu.

Gavrilescu avoided prison this time, as he hadn’t yet published his works. But he remained under watch by the Securitate and, unbeknown to him, Auroa, until, in 1985, he was stripped of his Romanian citizenship and forced into exile in Paris.

He lived with his wife in France until 1991, nursing her until she died from pancreatitis. In the airport on his way out of Romania a Securitate colonel collared him and said with a smile: “Watch where you’re going, bandit. The Securitate has long arms.”

Vasile Gavrilescu died on the sixth of August 2011 of a heart attack. He remarried but is said to have never fully recovered from reading his file. He wrote a book on his file and shared his story with the press, which caused a rift with the children he had with Aurora, sending him further into depression.

In one of his final interviews, with French paper Le Monde, he said: “Fortunately, when I found these things, my wife was already dead. I cannot forgive, nor forget.”

SHARES

Comments