The American essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson suggested, “money often costs too much.”

Though writing in the 19th Century, his words hold acute resonance today, especially to the ears of mega-rich sportsmen around the world who find their colossal wealth is wrestled from them shortly after retirement, thanks largely to unsustainable, opulent lifestyles and toxic investments.

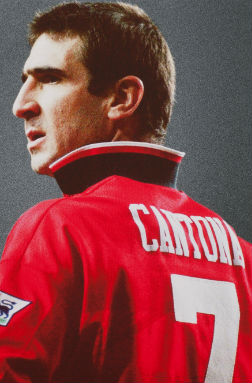

There is an ever growing list of affected sports stars either side of the Atlantic, including high-profile basketball players, boxers and NFL names as well as Premier League footballers and golfers.

Take Dennis Rodman, the former Chicago Bulls small forward with a penchant for dying his hair and befriending crazed despots, who earned an estimated $50m in his career, but was sunk by his flash spending – ironically aided by a 47ft speedboat tastefully christened ‘Sexual Chocolate’.

A string of divorces and childcare payments continue to singe his fingers. Attorney Linnea Willis has previously said the 53-year-old allegedly suffers from alcoholism and is barely able to cover his living expenses, and has been accused of owing nearly $1million in child and spousal support.

Rodman’s Bulls teammate Scottie Pippen was equally profligate with his fortune and at one point it seemed that he would endorse almost anything that came his way. A $4m deal for a Gulfstream jet also nose-dived in 2002. Due to a missed inspection, the jet’s engine needed $1m worth of repairs shortly after the purchase.

Rather than paying that, the jet was grounded, making it the world’s most expensive paperweight. Recently however, Pippen has taken exception to the rumours that he had actually gone broke, promising to sue any media outlet who defamed him.

Meanwhile, in May 2012, three-time All-Star Antoine Walker – who earned $110m in his 13-year career – was found to have debts of $12.7m, thanks to his casino visits and other vices.

But this famous trio are far from the only ones who have squandered vast sporting fortunes. In fact, according to Sports Illustrated, some 60 per cent of NBA players are forced to admit insolvency within five years of retirement.

And in the NFL there are more tales of woe, with a staggering 78 per cent of footballers bankrupted within just two years of hanging up their helmets. Mark Brunell, the ex-Jacksonville Jaguars quarter-back - a three-time Pro Bowl selection - earned £32 million but is now $25m in the red because of rotten business investments.

Additionally golfer John ‘Wild Thing’ Daly, the 1995 Open champion, drank and gambled away his $60m fortune. In one five-hour session on Las Vegas slot machines he frittered away $1.65m alone.

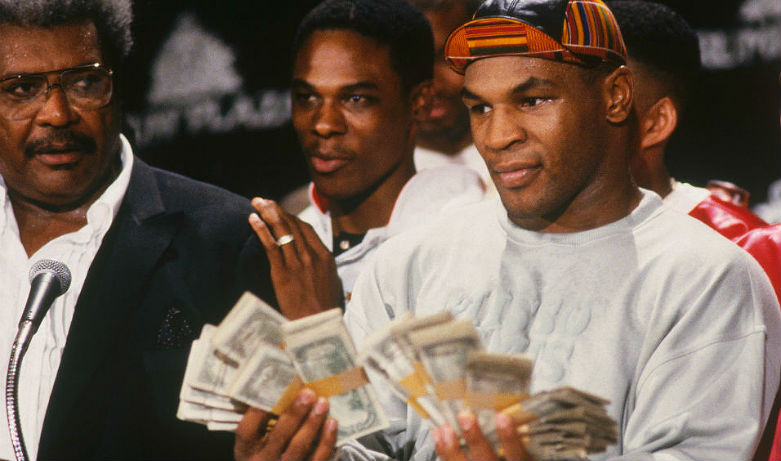

Then there are the two most recognisable heavyweight pugilists in the past 30 years: Evander Holyfield and Mike Tyson. The latter’s troubles have been well documented. Tyson filed for bankruptcy in 2003, and saw $400m vanish down the toilet, quite literally at one point, when he splashed out on an exotic bathroom suite; the bathtub alone set him back $2m.

Asked if he has enough money in the bank to tie him over between jobs, Tyson said, “No, I’m totally broke. I had a lot of fun. It (going broke) just happened.”

Meanwhile, Holyfield boxed his way to $250m but had to hand over his 109-bedroom mansion in 2008, blaming it on poor business decisions and two failed marriages.

The sporting stars of the fairer sex can find themselves in financial dire straits, too. Take Sheryl Swoopes, who was often compared to Michael Jordan on the basketball court. She scooped over $50m throughout her illustrious WNBA career, but filed for bankruptcy in 2004, citing mismanagement of her finances and poor investments.

Evander Holyfield’s 109-room Georgia mansion.

So how do mega-wealthy elite athletes lose it all? There are two main factors, according to Mark Sands, the head of the national bankruptcy team at RSM Tenon in London, who deal with Premier League footballers who flirt with insolvency.

Firstly, sports professional nearing the end of their careers – aged between 30 and 40 – struggle to balance their lavish outgoings with their significantly shrinking incomings. And when combined with high-risk investments, which bomb, this is an explosive mix.

“It may be a relatively small minority, but it still is astounding to see people who earn tens of thousands of pound a week going in to any form of insolvency,” says Sands. “More and more sportsmen have been coming to me in the past three or four years. I went through the recession of the early 1990s and it was totally different then. I don’t remember seeing professionals and stars in any number getting in to difficulty.”

These sportsmen have a very small earning window, and the fusion of poor financial knowledge (and the need to entrust their wealth with other supposedly more-canny advisors) and competitive extravagance - “keeping up with the Joneses,” as Sands calls it - can lead to unmanageable debt.

Ex-England goalkeeper and bankrupt David James recently sold all his career memorabilia to raise some cash.

Nowadays, there is more advice offered for retiring sports people than there was just a few years ago, but Sands believes it is falling on deaf ears, and not enough is being done to prepare footballers for life after their careers. He continues: “The clubs or the players’ agents should ensure they are putting aside a decent slice of their income for retirement.”

Oshor Williams, who runs a programme for the Professional Footballers’ Association called Making the Transition which deals with life after a football career, agrees, and says: “Those who are fortunate enough to play in the Premier League even for a relatively short period need to seek appropriate professional advice regarding the management of their financial affairs.”

A Hail Mary approach to finances by mega-rich sportsmen - and women - can leave them rueing their decision to go for broke, literally, and the adjustment from earning mega-bucks a week to next to nothing can be too tough for some. Money can, indeed, cost too much.

SHARES

Comments